-

Gold hits record, dollar drops as tariff fears dampen sentiment

Gold hits record, dollar drops as tariff fears dampen sentiment

-

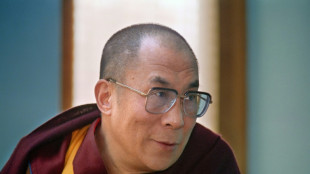

As Dalai Lama approaches 90, Tibetans weigh future

-

US defense chief shared sensitive information in second Signal chat: US media

US defense chief shared sensitive information in second Signal chat: US media

-

Swede Lingblad gets first win in just third LPGA start

-

South Korea ex-president back in court for criminal trial

South Korea ex-president back in court for criminal trial

-

Thunder crush Grizzlies, Celtics and Cavs open NBA playoffs with wins

-

Beijing slams 'appeasement' of US in trade deals that hurt China

Beijing slams 'appeasement' of US in trade deals that hurt China

-

Trump in his own words: 100 days of quotes

-

Padres say slugger Arraez 'stable' after scary collision

Padres say slugger Arraez 'stable' after scary collision

-

Trump tariffs stunt US toy imports as sellers play for time

-

El Salvador offers to swap US deportees with Venezuela

El Salvador offers to swap US deportees with Venezuela

-

Higgo holds on for win after Dahmen's late collapse

-

El Salvador's president proposes prisoner exchange with Venezuela

El Salvador's president proposes prisoner exchange with Venezuela

-

Gilgeous-Alexander, Jokic, Antetokounmpo named NBA MVP finalists

-

Thomas ends long wait with playoff win over Novak

Thomas ends long wait with playoff win over Novak

-

Thunder rumble to record win over Grizzlies, Celtics top Magic in NBA playoff openers

-

Linesman hit by projectile as Saint-Etienne edge toward safety

Linesman hit by projectile as Saint-Etienne edge toward safety

-

Mallia guides Toulouse to Top 14 win over Stade Francais

-

Israel cancels visas for French lawmakers

Israel cancels visas for French lawmakers

-

Russia and Ukraine trade blame over Easter truce, as Trump predicts 'deal'

-

Valverde stunner saves Real Madrid title hopes against Bilbao

Valverde stunner saves Real Madrid title hopes against Bilbao

-

Ligue 1 derby interrupted after assistant referee hit by projectile

-

Leclerc bags Ferrari first podium of the year

Leclerc bags Ferrari first podium of the year

-

Afro-Brazilian carnival celebrates cultural kinship in Lagos

-

Ligue 1 derby halted after assistant referee hit by projectile

Ligue 1 derby halted after assistant referee hit by projectile

-

Thunder rumble with record win over Memphis in playoff opener

-

Leverkusen held at Pauli to put Bayern on cusp of title

Leverkusen held at Pauli to put Bayern on cusp of title

-

Israel says Gaza medics' killing a 'mistake,' to dismiss commander

-

Piastri power rules in Saudi as Max pays the penalty

Piastri power rules in Saudi as Max pays the penalty

-

Leaders Inter level with Napoli after falling to late Orsolini stunner at Bologna

-

David rediscovers teeth as Chevalier loses some in nervy Lille win

David rediscovers teeth as Chevalier loses some in nervy Lille win

-

Piastri wins Saudi Arabian Grand Prix, Verstappen second

-

Kohli, Rohit star as Bengaluru and Mumbai win in IPL

Kohli, Rohit star as Bengaluru and Mumbai win in IPL

-

Guirassy helps Dortmund past Gladbach, putting top-four in sight

-

Alexander-Arnold lauds 'special' Liverpool moments

Alexander-Arnold lauds 'special' Liverpool moments

-

Pina strikes twice as Barca rout Chelsea in Champions League semi

-

Rohit, Suryakumar on song as Mumbai hammer Chennai in IPL

Rohit, Suryakumar on song as Mumbai hammer Chennai in IPL

-

Dortmund beat Gladbach to keep top-four hopes alive

-

Leicester relegated from the Premier League as Liverpool close in on title

Leicester relegated from the Premier League as Liverpool close in on title

-

Alexander-Arnold fires Liverpool to brink of title, Leicester relegated

-

Maresca leaves celebrations to players after Chelsea sink Fulham

Maresca leaves celebrations to players after Chelsea sink Fulham

-

Trump eyes gutting US diplomacy in Africa, cutting soft power: draft plan

-

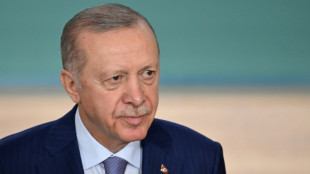

Turkey bans elective C-sections at private medical centres

Turkey bans elective C-sections at private medical centres

-

Lebanon army says 3 troops killed in munitions blast in south

-

N.America moviegoers embrace 'Sinners' on Easter weekend

N.America moviegoers embrace 'Sinners' on Easter weekend

-

Man Utd 'lack a lot' admits Amorim after Wolves loss

-

Arteta hopes Arsenal star Saka will be fit to face PSG

Arteta hopes Arsenal star Saka will be fit to face PSG

-

Ukrainian troops celebrate Easter as blasts punctuate Putin's truce

-

Rune defeats Alcaraz to win Barcelona Open

Rune defeats Alcaraz to win Barcelona Open

-

Outsider Skjelmose in Amstel Gold heist ahead of Pogacar and Evenepoel

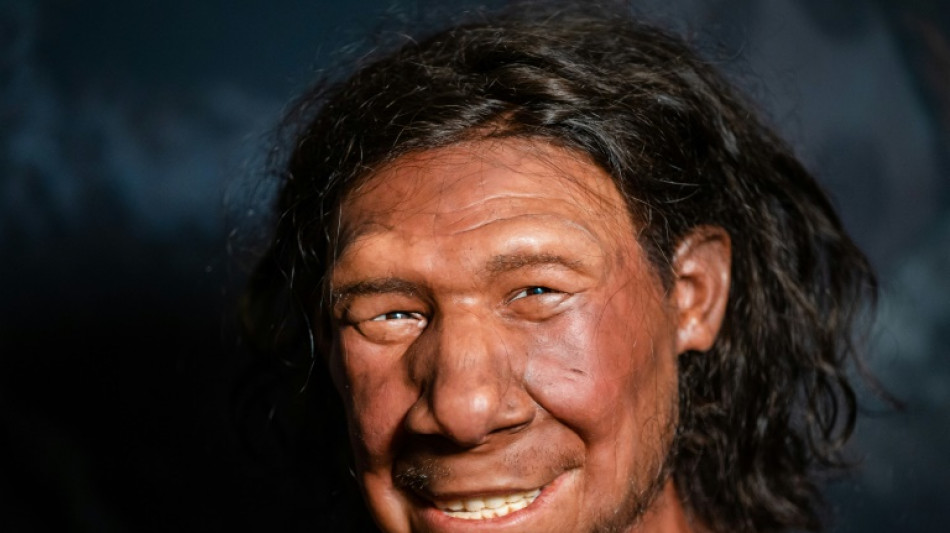

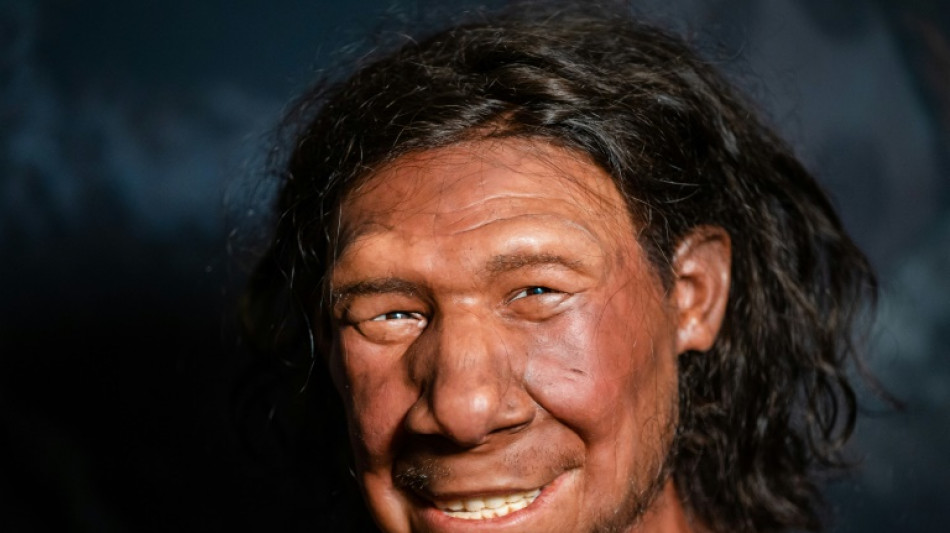

Was a lack of get-up-and-go the death of the Neanderthals?

A new study posits a very surprising answer to one of history's great mysteries -- what killed off the Neanderthals?

Could it be that they were unadventurous, insular homebodies who never strayed far enough from home?

Scientists studying the remains of a Neanderthal found in France said Wednesday that these human relatives were socially isolated from each other for tens of thousands of years, which could have fatally reduced their genetic diversity.

Up to now, the main theories for their demise were climate change, a disease outbreak, and even violence -- or interbreeding -- with Homo Sapiens.

Neanderthals populated Europe and Asia for a long time -- including a decent stint living alongside early modern humans -- until they abruptly died off 40,000 years ago.

That was the last moment when more than one species of human coexisted on Earth, French archaeologist Ludovic Slimak told AFP.

It was a "profoundly enigmatic moment, because we do not know how an entire humanity, which existed from Spain to Siberia, could suddenly go extinct," he said.

Slimak is the lead author of a new study in the journal Cell Genomics, which looked at the fossilised remains of a Neanderthal discovered in France's Rhone Valley in 2015.

The remains were found in Mandrin cave, which is known to have been home to both Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens over time.

The Neanderthal, dubbed Thorin in reference to the dwarf in J.R.R. Tolkien's "The Hobbit", is a rare find.

Thorin is the first Neanderthal unearthed in France since 1978 -- and one of only roughly 40 discovered in all of Eurasia.

- 50,000 years alone -

The archaeologists had spent a decade unsuccessfully trying to recover DNA from Mandrin cave when they found Thorin, Slimak said.

"As soon as the body came out of the ground," they sent a piece of molar to geneticists in Copenhagen for analysis, he added.

When the results came back, the team was stunned. Archaeological data had suggested the body was 40,000 to 45,000 years old, but the genomic analysis found it was from 105,000 years ago.

"One of the teams must have gotten it wrong," Slimak said.

It took seven years to get the story straight.

Analysing isotopes from Thorin's bones and teeth showed that he lived in an extremely cold climate, which matched an ice age only experienced by later Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago.

But Thorin's genome did not match those of previously discovered European Neanderthals at that time. Instead it resembled the genome of Neanderthals some 100,000 years ago, which had caused the confusion.

It turned out that Thorin was a member of an isolated and previously unknown community that had descended from some of Europe's earliest Neanderthal populations, the researchers said.

"The lineage leading to Thorin would have separated from the lineage leading to the other late Neanderthals around 105,000 years ago," senior study author Martin Sikora of the University of Copenhagen said in a statement.

This other lineage then spent a massive 50,000 years "without any genetic exchange with classic European Neanderthals," including some that only lived a two-week walk away, Slimak said.

- Dangers of inbreeding -

This kind of extended social isolation is unimaginable for the Neanderthals' cousins, the Homo Sapiens, particularly because the Rhone Valley then was a great migration corridor between northern Europe and the Mediterranean Sea.

Archaeological finds have long suggested that Neanderthals lived in a small area, ranging just a few dozen kilometres from their home.

Homo Sapiens, in comparison, had "infinitely larger" social circles, spreading over tens of thousands of square kilometres, Slimak said.

Neanderthals were also known to have lived in small groups -- so not venturing far likely meant there were not many options for a mate outside of their own family.

This kind of inbreeding reduces the genetic diversity in a species, which can spell doom over the long term.

Rather than single-handedly killing off the Neanderthals, their lack of intermingling could have made them more vulnerable to some of the other popular theories for their demise.

"When you are isolated for a long time, you limit the genetic variation that you have, which means you have less ability to adapt to changing climates and pathogens," said study co-author Tharsika Vimala, a population geneticist at the University of Copenhagen.

"It also limits you socially because you're not sharing knowledge or evolving as a population," she said.

F.Stadler--VB